History of German Wine

Introduction to German Wine

German wine has a rich and storied history spanning over two millennia, making it one of Europe's oldest winemaking traditions. Primarily produced in the western part of the country along the Rhine River and its tributaries, German viticulture is renowned for its cool-climate wines, particularly those made from Riesling, which thrive in the region's slate-rich soils and steep vineyards. Today, Germany boasts 13 designated quality wine regions (Anbaugebiete), covering about 104,000 hectares of vineyards and producing around 10 million hectoliters annually, ranking ninth globally in wine production. Whites dominate at about 66% of output, with reds at 34%, and the industry has shifted from mass-produced sweet wines to high-quality dry styles. Key grapes include Riesling (23.6% of plantings), Müller-Thurgau (10.6%), Spätburgunder (Pinot Noir, 11.1%), and others like Grauburgunder (Pinot Gris) and Silvaner. The history reflects influences from Roman conquests, monastic traditions, royal patronage, environmental challenges, and modern reforms driven by associations like the VDP (Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter).

Ancient Origins: Roman and Celtic Foundations

The roots of German wine trace back to the Celts and Romans, with viticulture emerging in what is now southwestern Germany. Wild vines (Vitis vinifera silvestris) grew along the upper Rhine as early as prehistoric times, but systematic cultivation began with Celtic influences around 200 BCE, though the oldest plantations are often attributed to Roman expansion. The Romans, who adopted winemaking from the Greeks and Etruscans, introduced organized viticulture during their northward conquests around 50 BCE, starting in the Mosel region—the country's oldest wine-growing area—and spreading to the Rhine. Archaeological evidence includes pruning knives from Roman garrisons dating to the 1st century AD near Trier (originally Augusta Treverorum, capital of the Western Roman Empire) and winepresses excavated in sites like Piesport, Brauneberg, and Erden.

The roots of German wine trace back to the Celts and Romans, with viticulture emerging in what is now southwestern Germany. Wild vines (Vitis vinifera silvestris) grew along the upper Rhine as early as prehistoric times, but systematic cultivation began with Celtic influences around 200 BCE, though the oldest plantations are often attributed to Roman expansion. The Romans, who adopted winemaking from the Greeks and Etruscans, introduced organized viticulture during their northward conquests around 50 BCE, starting in the Mosel region—the country's oldest wine-growing area—and spreading to the Rhine. Archaeological evidence includes pruning knives from Roman garrisons dating to the 1st century AD near Trier (originally Augusta Treverorum, capital of the Western Roman Empire) and winepresses excavated in sites like Piesport, Brauneberg, and Erden.Emperor Marcus Aurelius Probus (reigned 276–282 CE) is traditionally credited as the founder of German viticulture for repealing earlier bans on vine planting north of the Alps and promoting cultivation in the Agri Decumates region (modern Baden-Württemberg). The earliest written documentation comes from around 370 CE, when Roman poet Ausonius composed *Mosella*, a 483-hexameter poem extolling the steep vineyards along the Moselle River and the region's vibrant wine culture. By 570 CE, poet Venantius Fortunatus referenced red German wines, indicating early diversity in styles. Roman innovations, such as trellising systems like the Pfälzer Kammertbau (a comb-like structure traditional to the Palatinate), persisted into the 18th century. Wine was transported via ships, as evidenced by the 3rd-century Neumagen wine ship tomb, now replicated for tours in Neumagen-Dhron.

Medieval Period: Monastic Expansion and Charlemagne's Influence

The spread of Christianity in the 8th century propelled German winemaking forward, with monasteries becoming central hubs for viticulture and innovation. Before this, production was largely confined west of the Rhine. Emperor Charlemagne (reigned 768–814 CE), from his palace in Ingelheim, observed the Rheingau's southern slopes melting snow earlier than others, deeming them ideal for vines. He regulated viticulture, winemaking, and commerce, promoting Riesling's emergence in the Rheingau and establishing Strausswirtschaften—seasonal wine taverns marked by flower wreaths, a tradition still alive today. Monasteries, such as the imperial Lorsch Abbey (with ~900 vineyards by 850 CE), dominated production, replacing polluted water with wine as the primary beverage.

Key foundations included the Benedictine abbey at Schloss Johannisberg (1100 CE) by Archbishop Ruthard of Mainz and the Cistercian Kloster Eberbach (1135 CE) by Adalbert, both linked to Burgundy and Champagne traditions. Grape varieties documented from the 14th–15th centuries include Riesling (first mention as "Riesslingen" on March 13, 1435, in Rüsselsheim, Hessische Bergstrasse; now celebrated as Riesling's birthday), Spätburgunder (as Klebroth from 1318 on Lake Constance), Elbling, Silvaner, Muscat, Räuschling, and Traminer. Vineyards expanded dramatically during the Middle Ages, reaching their peak extent around 1500 CE—up to four times today's area—covering regions along the Mosel, Rhine, Nahe, Ahr, and even northern areas like Saxony.

Decline, Wars, and Early Modern Challenges

Decline, Wars, and Early Modern ChallengesFrom the 16th century, northern Germany's shift to beer reduced wine demand, while the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) devastated vineyards and dissolved monasteries in Protestant areas, eroding expertise. The Little Ice Age (roughly 1550–1850) made marginal northern and eastern sites unviable, leading to a sharp decline in plantings. Despite this, core regions persisted, and quality controls emerged, such as medieval punishments for adulteration (e.g., entombment in 1471) and decrees in 1498. The Heidelberg Castle's giant barrel (1751, holding 220,000 liters) symbolizes the era's grandeur, though it was filled only thrice.

Innovations and the Golden Age (17th–19th Centuries)

The 17th and 18th centuries marked a "golden age" for German wine, with Mosel and Rheingau bottlings fetching prices equal to or higher than Champagne and Bordeaux, favored by European royalty. The term "hock" for German whites originated from Hochheim am Main, popularized by Queen Victoria's 1850 harvest visit.

Pivotal innovations included the accidental discovery of Spätlese in 1775 at Schloss Johannisberg, where a delayed harvest led to noble rot-affected Riesling grapes producing sweet, high-quality wine; Auslese followed in 1787. This formed the basis of the Prädikat system (legalized in 1971), emphasizing ripeness levels like Kabinett, Spätlese, and Auslese. In 1787, Elector Clemens Wenceslas mandated Riesling replanting in the Mosel, creating the world's largest Riesling area. Ice wine (Eiswein) was born in 1830 in Dromersheim when frozen 1829 grapes, intended for cattle, yielded sweet juice upon pressing.

Napoleonic secularization (early 1800s) redistributed church vineyards, fragmenting them via inheritance laws and fostering cooperatives—the first in Mayschoß (Ahr) in 1867 amid economic crises. Phylloxera arrived in 1872 from North America, ravaging vineyards; grafting onto American rootstocks saved the industry, though many indigenous varieties were lost.

20th Century Challenges and the 1971 Wine Law

20th Century Challenges and the 1971 Wine LawTwo World Wars halved vineyard areas, diverted resources, and eroded international markets; Alsace-Lorraine was lost to France in 1919. Post-WWII recovery saw brands like Blue Nun dominate with sweet Liebfraumilch exports in the 1950s–1980s, but this reinforced stereotypes of cheap, sweet wines. The 1971 Wine Law, aligned with EU standards, defined regions and quality levels (Qualitätswein, Prädikatswein) but failed by not distinguishing superior single vineyards (Einzellagen) from lesser collective sites (Grosslagen), allowing undisclosed blending, and ignoring yield limits—leading to overproduction (90–100 hl/ha in the 1970s–1980s from high-yielding crossings) and quality dilution. Traditional yields had been lower (40–50 hl/ha from the 1930s–1960s).

New varieties emerged, like Scheurebe (1916, Riesling cross) and Müller-Thurgau (once dominant for yields). The VDP, founded in 1910 as VDNV to promote natural wines, sparked reforms, including the 1971 classification precursor.

Modern Renaissance: Reforms, Climate Change, and Global Recognition

Reunification in 1990 added eastern regions like Saale-Unstrut and Sachsen, completing 13 Anbaugebiete. A "quality revolution" in the 1990s shifted focus to dry wines (now 50–90% of production), with reds surging to 37% by the 2000s (e.g., Spätburgunder plantings stable at 11.1%, Dornfelder at 6.6%). Riesling's renaissance in 1995 positioned Germany as the top producer (over 60% market share).

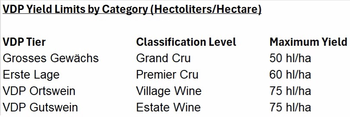

Over the last twenty years (circa 2006–2026), reactions to the 1971 Law's flaws have driven improvements: The VDP's 2002 classification emphasized site-specificity with Grosses Gewächs (GG, "Grand Cru" dry wines from top sites, capped at 50 hl/ha, hand-harvested, Spätlese ripeness), restricting to traditional varieties like Riesling and limiting yields (secondary tiers at 65 hl/ha). In 2012 the VDP moved from a three-tier system to the current four-tier pyramid that mimics the Burgundy model (Grand Cru, Premier Cru, Village, Estate). The three additional tiers in descending order of quality are: VDP Erste Lage (Premier Cru), VDP Ortswein (village wine) and VDP Gutswein,(estate wine). Yields for the "secondary tiers" are as follows:

Terms like "Classic/Selection" (2000, for dry, high-alcohol wines) and "feinherb" (off-dry) emerged, alongside Eiswein as a separate category since 1982. Climate change has reduced poor vintages (only 2000 notably weak since 2000), increased ripeness for drier styles without losing acidity, and enabled fuller fermentation.

Organic/biodynamic farming has grown to over 7,000 hectares (4–5% market share), ranking Germany sixth worldwide. Young winemakers (e.g., Generation Riesling, formed 2006) adopt global techniques, modern equipment, and pairings with spicy foods. Institutions like Geisenheim University (formalized 2013, roots in 1872) advance research. Today, Germany exports to the US, Netherlands, and UK, with a craft focus (14,150 small owners, many cooperatives producing one-third of output). Innovations include barrique-aged reds, Sekt sparkling wines, and rosés, while sweet Prädikats remain iconic.